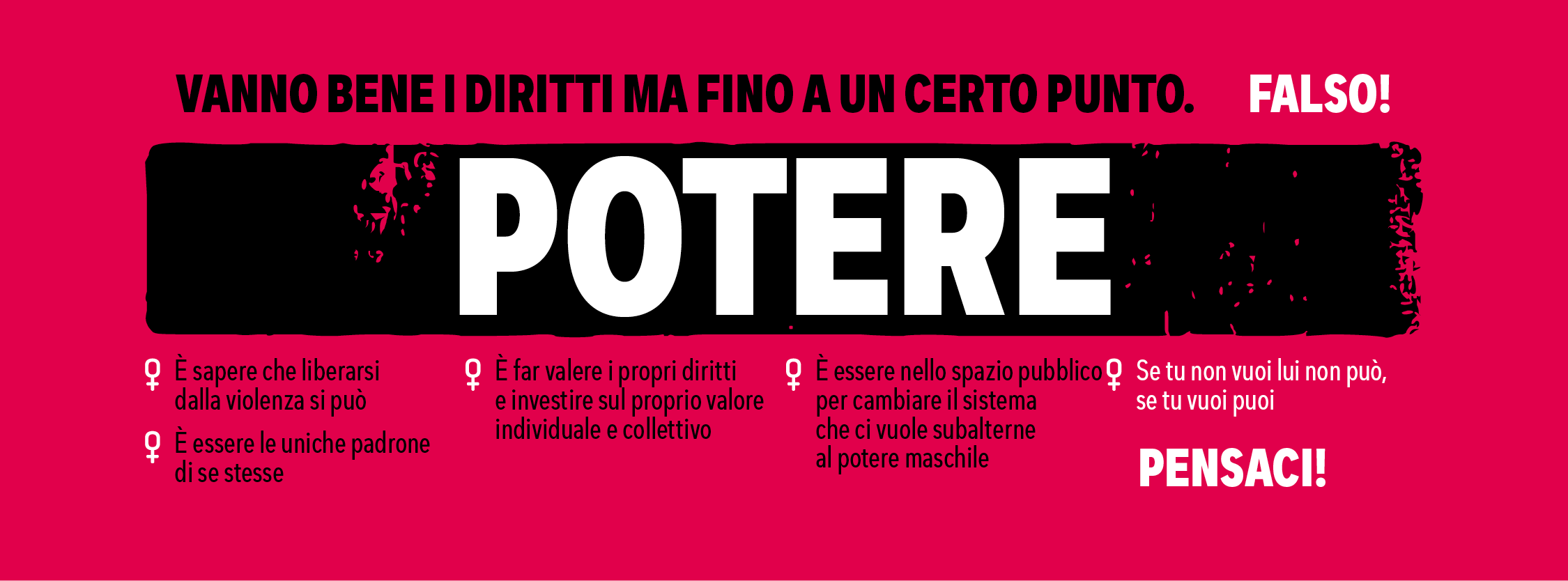

Basta la parola: potere

Potere

Il potere patriarcale nel pubblico

Da secoli le donne vivono una condizione di subalternità, disuguaglianza, svantaggio, segregazione, fondata sull’appartenenza di genere, cioè sul fatto di essere femmine.

Il soggetto di paragone che dà senso al termine disparità è l’uomo in quanto maschio.

Si parla spesso e si è sentita sempre più di frequente negli ultimi decenni l’espressione “potere maschile”, “potere patriarcale”, riferimento del pensiero femminista.

“Potere” è un termine che come sostantivo o come verbo acquisisce significati diversi, per quanto connessi e somiglianti. Ha un’accezione positiva o negativa a seconda del contesto. Mentre il sostantivo è spesso percepito come uno spazio che si occupa in virtù di un ruolo, il verbo introduce a una vista che va oltre e afferisce alla possibilità di poter far qualcosa (per es. per aiutare, risolvere un problema, produrre un cambiamento).

Se il potere rappresenta la base di uno schema di relazione convenuto e riconosciuto, è la parola chiave che svela i rapporti di forza in un sistema. Ne è quindi fattore strutturale.

Nel rapporto fra i sessi schemi predefiniti attribuiscono un ruolo alle donne e un ruolo agli uomini stabilendo un destino per ciascuno dei generi.

Quello previsto per le donne lascia margini ristrettissimi di autodeterminazione nella scelte di vita. Madri, sorelle, mogli, sono i ruoli/condizione che si attribuiscono alle donne, sempre viste, giudicate, valutate attraverso di essi. Lo si riscontra da come i media parlano e scrivono (a prescindere dai fatti che inducono l’attenzione mediatica). Siamo nella sfera privata quella della cura degli altri (figli, genitori, altri congiunti) l’ambito di eccellenza in cui, secondo la cultura patriarcale, le donne possono e devono esprimersi e realizzarsi. Una collocazione marginale nel sistema sociale, politico, istituzionale dove si prendono le decisioni che riguardano l’intera comunità. “La regina della casa”, “la padrona di casa”, “quella che si prende cura e su cui si fonda la famiglia” sono frasi sentite innumerevoli volte per sottolineare la missione affidata alle donne.

Agli uomini lo spazio pubblico dove si decidono le sorti del Paese e della società. In questo spazio le donne sono ancora largamente in minoranza pur essendosi verificati miglioramenti negli ultimi decenni.

Il potere disuguale nel sistema era sancito dall’ordinamento giuridico là dove si prevedeva il delitto d’onore (in caso di violenze l’oggetto di tutela era l’onore maschile), il matrimonio riparatore (in caso di stupro il matrimonio riparava l’offesa e la violenza in una unione combinata che ripristinava la regola sociale), lo stupro reato contro il pudore (l’oggetto tutelato dalla norma era il pudore e non la donna che subiva violenza), l’esclusione delle donne da diritti patrimoniali, la patria potestà (il nome è eloquente) negata alle donne fino all’entrata in vigore del nuovo diritto di famiglia nel 1975, il suffragio universale inteso come solo maschile fino al 1945 quando fu riconosciuto il diritto di voto alle donne. Si potrebbero fare molti altri esempi.

Queste disuguaglianze e le norme che collocavano le donne in una posizione chiaramente subalterna negandole come soggetti di diritto e persone sono state contrastate nel tempo dai movimenti femminili e femministi che hanno ottenuto cambiamenti fondamentali nell’ordinamento giuridico con lotte dure e radicali. Si sono verificati cambiamenti culturali importanti, parte dei quali erano già avvenuti di fatto al momento del recepimento in leggi dello Stato. La mentalità e il senso comune erano già parzialmente evoluti trovando corrispondenza nella Costituzione italiana. Oggi tuttavia molte leggi rimangono in gran parte o totalmente inapplicate. Si mantiene così di fatto la condizione di disuguaglianza fra uomini e donne, anche denominata Gender gap.

Si obietterà che oggi le donne nei luoghi di potere sono più numerose. Il ché è innegabile ma fino a quando questa maggiore presenza non si risolverà a favore del miglioramento della condizione e dei pari diritti e opportunità per tutte sarà insufficiente a superare il gender gap. Anzi è probabile, come spesso accade, che la collocazione di donne in posizioni di potere si traduca in un vantaggio individuale e rafforzi una logica competitiva che finisce comunque per penalizzare le donne. L’introduzione delle quote, salutate come rimedio, almeno parziale, rischia di tradursi in una nuova forma maschile di controllo e di calmierazione del conflitto di genere, viste le leggi elettorali vigenti e le cariche di potere che decidono le nomine per lo più ricoperte da uomini.

Il potere patriarcale nel privato

In ambito privato, domestico, famigliare il potere patriarcale si esprime con il controllo sulla vita e sul corpo delle donne.

Come si rileva troppo spesso, la violenza sulle donne ne è una conseguenza. Si arriva alle estreme conseguenze col femminicidio quando una donna decide di rifarsi una vita, di mettere termine a una relazione affettiva. Diversi uomini non sopportano la decisione delle compagne di essere libere di scegliere e autodeterminare la propria vita.

Un rapporto che si esaurisce, mette fine a una relazione di potere che scambia il senso di possesso con l’amore e l’affettività. L’uomo perde un potere sulla compagna vissuto come un vulnus, un’offesa inaccettabile da punire per ripristinare la regola cioè la sua supremazia. I ricatti affettivi o peggio sui figli, le violenze fisiche, psicologiche, economiche, le minacce e le pressioni continue (stalking) ne sono le manifestazioni diffuse.

Questa mentalità rivela da un lato la fragilità maschile e la difficoltà a gestire le emozioni e i sentimenti, ma anche una concezione del ruolo delle donne prevalentemente funzionale al benessere degli uomini. Il consenso espresso al momento della nascita di una relazione e ancor più del matrimonio è concepito come incondizionato e permanente.

Tale visione sottende il rifiuto e l’inaccettabilità della donna come soggetto di diritto e di libertà di scelta, capace di decidere, come sancito dalla Costituzione.

In altre parole per molti uomini non è “normale” che la propria compagna scelga in autonomia un percorso di vita che non li include.

Le donne sono molto spesso colpevolizzate per le scelte che fanno o che non fanno quando subiscono violenza in qualsiasi forma. Si tratta di vittimizzazione secondaria che si riscontra nell’attenzione quasi ossessiva sui loro comportamenti, sul loro passato, quando si fa il processo alle intenzioni e si ipotizzano da parte loro secondi fini.

Sostiene questa visione un’immagine che alimenta luoghi comuni stereotipati con rappresentazioni frequenti del corpo femminile oggetto di piacere e di desiderio del maschio quindi di per sé provocatorio e seducente. La si riconosce nella narrazione mediatica, nella comunicazione pubblicitaria, nelle esternazioni dell’immaginario maschile anche quando esse si manifestano con appellativi o espressioni considerate gentili, di apprezzamento , “normali”.

Il potere maschile e gli stereotipi sessisti hanno molte facce spesso camuffate da normalità. Si possono riconoscere con un altro sguardo sulla realtà e la consapevolezza.

Il potere nel pubblico e il potere nel privato si sostengono e si legittimano a vicenda alimentando una logica di sistema.

Per questo la violenza sulle donne è un problema culturale non di ordine pubblico nè si combatte con pene sempre più severe e repressive, ma con una cultura paritaria delle relazioni e di rispetto che non giustifica le condotte violente con l’amore.

Le donne possono liberarsi dalla violenza esercitando il potere su di sé. Gli uomini possono liberarsi dalla violenza rinunciando ai privilegi e al potere che mortificano e umiliano le donne: se lei non vuole tu non puoi. Se lei prende una decisione, la rispetti.

Power

Patriarchal power in public life

For centuries, women have lived in a condition of subordination, inequality, disadvantage and segregation based on their gender, i.e. on the fact that they are female.

The subject of comparison that gives meaning to the term “disparity” is the man as a male.

The expressions “male power” and “patriarchal power”, which refer to feminist thinking, have been used frequently and increasingly in recent decades.

“Power” is a term that, as a noun or verb, acquires different meanings, however connected and similar they may be. It has a positive or negative connotation depending on the context.

While the noun is often perceived as a space occupied by a role, the verb introduces a view that goes beyond this and relates to the possibility of being able to do something (e.g. to help, to solve a problem, to bring a change).

If power represents the basis of an agreed and recognised relationship pattern, it is the key word that reveals the power dynamic in a system. It is therefore a structural factor.

In the relationship between the sexes, predefined patterns assign a role to women and a role to men, establishing a destiny for each gender.

The role assigned to women leaves very little room for self-determination in life choices. Mothers, sisters, wives: these are the roles/conditions attributed to women, who are always seen, judged and evaluated through them. This can be seen in how the journalists talk and write (regardless of the facts that attract media attention). We are in the private sphere, the one that referrs to caring for others (children, parents, other relatives), the area of espertise in which, according to patriarchal culture, women can and must express themselves and fulfil themselves. A marginal position in the social, political and institutional system where decisions affecting the entire community are made. “The queen of the house”, “the lady of the house”, “the one who takes care of the family and is its foundation” are phrases heard countless times to emphasise the mission entrusted to women. Men occupy the public sphere where the fate of the country and society is decided. In this sphere, women are still very much in the minority, despite improvements in recent decades.

The unequal power within the system was enshrined in the legal system, which provided for honour killings (in cases of violence, the object of protection was male honour), reparatory marriage (in cases of rape, marriage repaired the offence and violence in an arranged union that restored social order), rape as a crime against modesty (the object protected by the law was modesty and not the woman who suffered violence), the exclusion of women from property rights, the parental authority (the name speaks for itself) denied to women until the new family law came into force in 1975, universal suffrage intendes as only male until 1945 when women were granted the right to vote. Many other examples could be given.

These inequalities and the norms that put women in a clearly subordinate position, denying them as subjects of law and persons, have been challenged over time by women's and feminist movements, which have achieved fundamental changes in the legal system through hard and radical struggles. Meanwhile important cultural changes have taken place, some of which had already occurred at the time of their transposition into state law. Mentalities and common sense had already partially evolved, finding correspondence in the Italian Constitution. Today, however, many laws remain largely or totally unenforced. This perpetuates the condition of inequality between men and women, also known as gender gap.

It could be argued that there are more women in positions of power today. This is undeniable, but until this greater presence leads to an improvement in the status and equal rights and opportunities for all, it will be insufficient to overcome the gender gap. Indeed, it is likely, as is often the case, that the placement of women in positions of power will translate into an individual advantage and reinforce a competitive logic that ultimately penalises women. The introduction of quotas, hailed as a remedy, at least in part, risks to be translated into a new form of male control and suppression of gender conflict, given the electoral laws in force and the positions of power that decide the nominatios, which are mostly held by men.

Patriarchal power in private life

In private, domestic and family life, patriarchal power is expressed through control over women's lives and bodies.

As is too often the case, violence against women is a consequence of this. This reaches its extreme consequences in femicide when a woman decides to rebuild her life and end a romantic relationship. Many men cannot bear their partners' decision to be free to choose and determine their own lives.

A relationship that ends puts an end to a power dynamic that confuses a sense of possession with love and affection. The man loses power over his partner, which he experiences as a wound, an unacceptable offence that must be punished in order to restore the rule, i.e. his supremacy. Emotional blackmail or worse, involving the children, physical, psychological and economic violence, threats and constant pressure (such as stalking) are widespread manifestations of this.

This mentality reveals, on the one hand, male sentimental fragility and difficulty in managing emotions and feelings, but also a conception of the role of women as primarily functional to the well-being of men. The consent expressed at the beginning of a relationship and even more so at the beginning of marriage is conceived as unconditional and permanent.

This view implies the rejection and unacceptability of women as subjects of rights and freedom of choice, capable of making decisions, as enshrined in the Constitution.

In other words, for many men, it is not “normal” for their partner to independently choose a path in life that does not include them.

Women are very often blamed for the choices they make or do not make when they suffer violence in any form. This is called secondary victimisation, which can be seen in the almost obsessive attention paid to their behaviour and their past, when their intentions are scrutinised and ulterior motives are assumed on their part.

This view is supported by an image that fuels stereotypical clichés with frequent representations of the female body as an object of male pleasure and desire and therefore inherently provocative and seductive. This can be recognised in media narratives, in advertising, in expressions of the male imagination, even when they manifest themselves in terms or expressions considered polite, of appreciation or “normal”. Male power and sexist stereotypes have many faces, often disguised as normality. They can be recognised with a different perspective on reality and awareness.

Power in the public sphere and power in the private sphere support and legitimise each other, fueling a systemic logic.

This is why violence against women is a cultural problem, not a matter of public order, and cannot be fought with increasingly severe and repressive penalties, but with a culture of equal relationships and respect that does not justify violent behaviour with love.

Women can free themselves from violence by exercising power over themselves. Men can free themselves from violence by giving up the privileges and power that mortify and humiliate women: if she does not want to, you cannot. If she makes a choice, respect it.

السلطة

السلطة الأبوية في المجال العام

منذ قرون تعيش النساء في وضعية تبعية، ولا مساواة، وحرمان، وعزل، بناءً على جنسهن، أي لمجرد كونهنّ إناثًا.

موضوع المقارنة الذي يُعطي معنىً لمصطلح عدم المساواة هو الرجل بصفته ذكر

في العقود الأخيرة كثر الحديث عن "السلطة الذكورية" و"السلطة الأبوية"، مرجعا للفكر النسوي

إن كلمة “سلطة” سواءا كانت إسما أو فعلا، يكتسب معاني مختلفة رغم ترابطها وتشابهها. وقد تحمل دلالة إيجابية أو سلبية حسب السياق. فبينما يُنظر إلى الاسم كمفهوم يشغَل مساحة بحكم الدورٍ الذي يؤديه، فإنّ الفعل يقدّم رؤية تتجاوز ذلك وتشير إلى إمكانية القيام بشيء ما (مثلاً للمساعدة، لحلّ مشكلة، لإحداث تغيير)

إذا كانت السلطة تمثل أساسًا لنظام علاقات مُعترف بها ومتوافق عليها، فهي الكلمة المفتاح التي تكشف موازين القوى داخل النظام. وهي بالتالي تشكل عنصرًا هيكليا فيه

في العلاقة بين الجنسين، تُسند أدوار محددة للنساء وأخرى للرجال، بحيث تَرسُم لكل جنس مصيرًا محددًا

الدور المتصور للنساء يقيّد بدرجة كبيرة القدرة على تقرير المصير في اختيارات الحياة. أمّهات، أخوات، زوجات: هذه هي الأدوار/المكانات المنسوبة للنساء، والتي من خلالها يتم النظر إليهن والحكم عليهن . يتضح ذلك في كيفية تناول وسائل الإعلام لمواضيعها وطريقة كتابتها (بغض النظر عن الحقائق التي أثارت الاهتمام الإعلامي). نحن إذن داخل المجال الخاص مجال رعاية الآخرين (الأطفال، الوالدين، الأقرباء)، وهو المجال الذي، بحسب الثقافة الأبوية، " ينبغي " للنساء أن يتجلّين فيه ويحققن ذواتهن من خلاله. مكانة هامشية داخل النظام الاجتماعي، السياسي، والمؤسساتي، حيث تُتخذ القرارات التي تخص المجتمع بأكمله. "ملكة البيت،" سيدة المنزل"، التي تقوم بالرعاية ويقوم عليها كيان الأسرة"، هي عبارات تستخدم مرات متعددة للإشارة إلى المهام الموكولة للنساء.

يحتل الرجال المجال العام حيث يُقرر مصير البلاد والمجتمع. في هذا المجال، لا تزال النساء تحتل نسبا ضئيلتا جدا، على الرغم من التحسينات التي شهدتها العقود الأخيرة

اللامساواة في السلطة كانت مُكرّسة من طرف المنظومة القضائية، ويمكن تمثيل ذلك في جريمة الشرف (حيث كان الشرف الذكوري هو موضوع الحماية)، الزواج الإصلاحي (حيث يُعاد "ترميم" العِرض بعد الاغتصاب بزواج مدبر يعيد القاعدة الاجتماعية)، الاغتصاب جريمة مُسيئة للحياء (الهدف الذي يحميه القانون هو الحياء، وليس المرأة التي تعرضت للعنف)، حرمان النساء من الحقوق المالية، من الولاية الأبوية (والاسم بحد ذاته واضح الدلالة) إلا بعد دخول قانون الأسرة الجديد حيّز التنفيذ عام 1975، إضافة إلى اعتبار "الاقتراع العام" حكراً على الرجال حتى عام 1945 حين مُنحَ حقّ التصويت للنساء. ويمكن ذكر أمثلة كثيرة أخرى من هذا القبيل.

هذه اللامساواة وهذه القوانين التي كانت تضع النساء في موقع تبعي صريح ومنعتهن من أن يكنّ أشخاصاً ذوات حقوق، قاومتها الحركات النسائية والنسوية على مر السنين، وحققت تغييرات قانونية أساسية عبر نضالات صعبة وجذرية. وقد حدثت تغييرات ثقافية مهمة، جزء منها قد تحقّق فعليا قبل أن تتبنّاه الدولة في قوانينها. فقد تطوّر الوعي المشترك والسلوك العام جزئياً، بما ينسجم مع الدستور الإيطالي. إلا أنّ كثيراً من القوانين اليوم ما تزال غير مُطبّقة أو مطبّقة جزئياً، مما يُبقي حالة من اللامساواة بين الرجال والنساء، والمسمّاة أيضاً الفجوة بين الجنسين

قد يُقال إنّ النساء اليوم أكثر حضوراً في مواقع السلطة. وهذا صحيح، لكن ما لم يتحوّل هذا الحضور المتزايد إلى تحسين فعلي في أوضاع النساء وحقوقهن وفرصهن، فسيبقى غير كافٍ لإزالة الفجوة بين الجنسين. من المرجح، كما يحدث غالبًا، أن يُترجم وضع النساء في مناصب السلطة إلى ميزة فردية ويعزز العقلية التنافسية التي تُضرّ بهن في نهاية المطاف. إن إدخال نظام الحصص -الكوتا-والذي اعتُبر حلاً جزئياً قد يتحوّل إلى شكل جديد من أشكال السيطرة الذكورية ووسيلة لامتصاص الصراع بين الجنسين، خصوصاً في ظلّ القوانين الانتخابية القائمة على إعطاء مناصب أكبر للرجال.

السلطة الأبوية في المجال الخاص

في المجال الخاص، المنزلي، العائلي، تتجلى السلطة الأبوية في التحكم بحياة النساء وأجسادهن.

كما هو شائع، العنف ضد النساء ما هو إلا نتيجة. تحدث العواقب الوخيمة "قتل النساء" عندما تقرر المرأة إعادة حياتها، أو تقرر إنهاء علاقة عاطفية. كثير من الرجال لا يطيقون قرار شريكتهم في اختيار وتحديد مصار حياتها.

علاقة منتهية، تعني انتهاء علاقة سلطة كانت قائمةً على القوة تخلط بين التملك والحب والمودة، يفقد الرجل سلطته على شريكته، فيُعتبر ذلك جرحًا، وإهانة مرفوضةً يجب معاقبتها لاستعادة هيمنته. الابتزاز العاطفي، أو أسوأ من دلك استغلال الأطفال، والإيذاء الجسدي والنفسي والمالي، والتهديدات، والضغط المستمر (الملاحقة)، هي مظاهرَ شائعةً للعنف.

تكشف هذه العقلية، من جهة، عن هشاشة الرجل وصعوبة تحكمه في مشاعره وانفعالاته، وتكشف أيضًا عن تصور لدور المرأة يركز في المقام الأول على رؤية وظيفيًة لخدمة راحة الرجل. فالموافقة المُعبّر عنها في بداية العلاقة، وخاصةً عند الزواج، تُعتبر غير مشروطة ودائمة

هذه الرؤية تجسد فكرة إنكار المرأة كفاعل حرّ يملك الحق في الاختيار، قادر على اتخاذ قراراته، كما جيء به في الدستور. بعبارة أخرى، بالنسبة للعديد من الرجال، ليس من "الطبيعي" أن تختار شريكة حياته مسار حياة مستقل لا يشمله.

وغالبا ما تحمل النساء مسؤولية اختياراتهن عندما يتعرضن لأي شكل من أنواع العنف. يتعلق الأمر بالتعنيف الثانوي الذي يظهر في التركيز شبه الهوسي على سلوكهن وماضيهن، حين تتم محاكمتهن على نواياهن وافتراض دوافع خفية من طرفهن.

تدعم هذه الرؤية الصورة النمطية من خلال تمثيل جسد المرأة كأداة للمتعة والرغبة الذكورية، وبالتالي يعتبر مُستفِزا و مغر بطبيعته. ويتجلى هذا في السرديات الإعلامية، والإعلانات، وفي التعبيرعن المعتقدات الفكرية للرجل، حتى حين يتم التعبير عنها بمصطلحات وتعابير ومجاملات مهذبة، تعبر “طبيعية"

للسلطة الذكورية والصور النمطية الجنسية وجوه عديدة، مخفية في غالب الأحيان وراء مظاهر طبيعية. يمكن تمييزها من خلال الوعي والنظر من زاوية مختلفة.

السلطة في المجال العام والسلطة في المجال الخاص تتكاملان وتُضفي كل منهما الشرعية على الأخرى، معززين المنطق البنيوي للنظام.

ولذلك فإن العنف ضد النساء قضية ثقافية وليست قضية أمنية، ولا يمكن محاربتها من خلال عقوبات زجرية مشددة، بل برؤية قائمة على المساواةفيالعلاقات والاحتراموالتيلاتبررأعمالالعنفبالحب.

يمكن للنساء التحرر من العنف بممارسة السلطة على ذواتهن.ويمكن للرجال التحرر منالعنف بالتخلي عن الامتيازات والسلطة التي تُهين النساء:إن لم تُرِدْ، فلا يحقّ لك.وإذا اتخذت قرارًا، فعليك احترامه.